Garden orientalism

The landscape garden, as well as a succession of paintings, is a showcase of curiosities, an encyclopaedia en plein air.

Landscape gardens are home to picturesque views and curiosities, creating an en-plein-air visual encyclopaedia. The term “fabrique” designates “all buildings of effect and all the constructions which human work adds to nature for the embellishment of gardens” (Morel 1776). In its panoramic connotation, the garden is a place for a peaceful coexistence of Classicism and Gothic Revival, of East and West. Walking through a garden is like embarking on a journey of sorts.

The most popular garden architectures were the exotic ones and it is no coincidence that the Prince of Ligne considered the “fabriques” as authentic anti-classic war machines.

In the eyes of westerners, the East has always been a fascinating and fanciful part of the world, capturing the imagination of writers, explorers and missionaries, inspiring artistic flights of fancy about faraway countries as well as many collections. Philosophy, poetry and painting certainly contributed to the rise of landscape gardens, but so did the new trend that favoured chinoiseries, reflecting aesthetic motivations combining with philosophical and political connotations.

The taste for exoticism that took over the garden scene from the end of the 18th century and throughout the 19th century, led to a proliferation of unusual architectures drawing from a repertoire of bizarre and eccentric models.

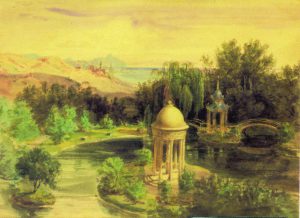

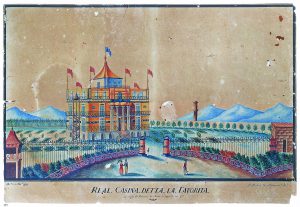

The so-called Casina Cinese (small Chinese house) in the park of the Real Favorita in Palermo, where Queen Maria Carolina, wife of Ferdinand IV of Bourbon used to reside, Villa Melzi d’Eril’s Moorish kiosk-belvedere on Lake Como, and the pagoda and small Chinese bridge reflecting in the small lake of Villa Durazzo Pallavicini in Pegli are but some examples.

Share on social

Share on social